I wrote most of this piece six months ago but got side-tracked (as usual!) before I’d finished tying up loose ends. Then, quite by chance, two things happened within a week: I had an email from a descendant of Caroline Holton; and I came across a newspaper cutting (The Bucks Herald of 1st March 1873), reporting on the inquest into another of the people who drowned.

I wrote most of this piece six months ago but got side-tracked (as usual!) before I’d finished tying up loose ends. Then, quite by chance, two things happened within a week: I had an email from a descendant of Caroline Holton; and I came across a newspaper cutting (The Bucks Herald of 1st March 1873), reporting on the inquest into another of the people who drowned.

[The account of the wreck comes from the Maritime Moments website, to whom I am greatly indebted.]

Some years ago I contributed notes and annotations to a book entitled “From Tingewick to Tioga” – the last few copies still available by emailing author Jan Anderson on janeandrs ‘at’ gmail.com. It was based on an account of the Holton family, written in 1917 by Joseph T. Holton whose father had emigrated from Tingewick to Pennsylvania in 1851. One of his notes said:

“My aunt, Caroline Holton was born 1826 and she married John _________ and they had children born unto them and they was drownded in the North Sea in 1873 and one child was safe in a boat and was adopted by people near Dover, but they say it died. But they say that they left two girls and they married two brothers named Day and that they went to London, but they have not heard.”

Caroline had, in fact, married John Taplin in October 1848 at Tingewick. He was probably working on the railway line, which was built across the northern edge of the parish around 1847. They had six daughters in the next twelve years. The second was baptised in Tingewick but died in infancy: the two youngest were twins, born in 1862.

The family was constantly on the move: Welling in Hertfordshire in 1849; Whatlington in Sussex in 1851; Dudley, Worcestershire in 1854; Tiveydale in Staffordshire in 1859; Bakewell in Derbyshire in 1861; Rosebury in Derbyshire in 1862; and Finsbury in London in 1871. By 1873, perhaps the boom in railway work in England had ended. John signed up to work on the Tasmanian Railroad, and – with his wife and three youngest daughters – boarded the Northfleet in London. On board were 379 people (including the crew and the pilot), 340 tons of iron rails, and 240 tons of other equipment, bound for Hobart in Tasmania. At 11 am on January 13 1873, she slipped down the river from London.

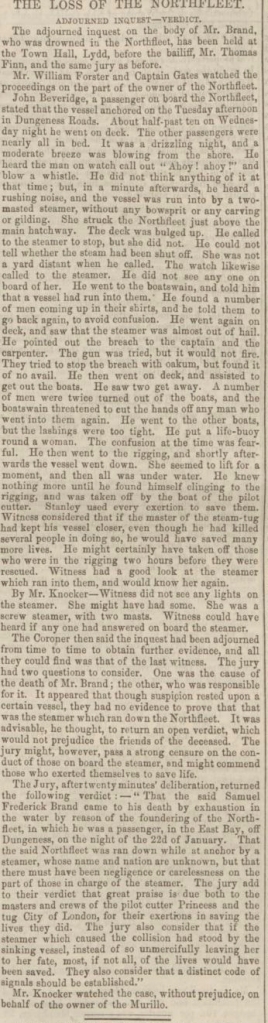

The late January weather was stormy and more than a week later they had only reached Dungeness, where they spent the night of the 22nd at anchor, in company with perhaps 300 other boats waiting for the weather to lift. Sometime after midnight, disaster struck – a steamer ran into them, striking them hard on the starboard side. Without identifying herself, the steamer backed away and vanished into the night.

For whatever reason, only two of the seven lifeboats were launched. Perhaps there wasn’t time (from the inquest I just found, ‘the lashings were too tight’) – within 30 minutes, the boat had sunk. In spite of the captain’s best efforts (including, apparently, shooting a man in the knee who disobeyed his orders), only two women, one child and one baby were saved. The rest of the 86 survivors were all men, including 11 of the crew. So much for women and children first! In all, 293 lives were lost: 41 were women; 43 were children; and 7 were babies under 1 year old.

The one child that was saved was Maria Taplin. It seems they were soon picked up by a steam tug, the City of London, and taken to the Seaman’s Mission in Dover. The captain’s wife – now widowed – offered to take Maria to London: the newspapers printed her story, and offers to adopt her poured in. Some versions say she went to live with her older sisters, now married: but the death registered in Dover in the third quarter of 1879 of a 17-year old Maria Taplin is probably hers.